Excerpt from the film:

GSP: poetry, music and more

An interview with Asha Ogale (1936-2025) on 18 March 2023

Let me start by telling you how I began working with Guy Poitevin.

I began working with Dr Guy and Hema Rairkar in 1983. I translated academic papers from French to English for him. I also translated Marathi articles into English whenever he needed me to. This went on for two or three years. However, after the formation of the Centre for Cooperative Research in Social Sciences (CCRSS), the field workers and activists of the Garib Dongari Sanghatana (GDS) started collecting information about their own villages and communities. They would also collect stories, myths, legends and folklore, which they would bring to me. I would then translate this material from Marathi into English. I also helped them set up their library. This kind of work continued until 1996.

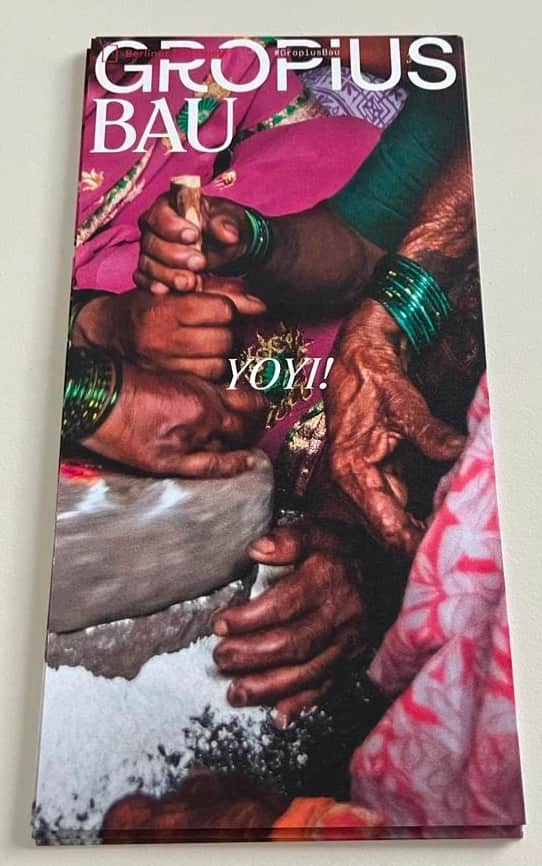

Around that time, they started collecting ovi (grindmill songs) from women in their area. I was not directly involved in this work. Field workers visited villages and collected these songs. Whenever Guy needed these ovis as references for his academic work or articles, he gave me sets of five or six ovis and I translated them into either English or French.

I often told Guy that I doubted my ability to do this work. But he convinced me that I could do it. He then discussed the form in detail with me. He also helped me to understand these songs properly. He explained the social and cultural context of the selected songs. I used to translate the lyrics, but I was unaware of how he worked on those translations or how he used the songs in his work. In a sense, my responsibility was limited to translating the songs.

In 1997, he introduced me to another organisation, Anthra Trust, after which I lost touch with this work for almost ten years. Guy passed away during that period. Around 2008, I received an urgent call from Hema Rairkar. She asked me to visit her as she was unwell. When I went to see her, she told me about her plans to continue her work on the ovi. She said that I was going to coordinate it. Again, I told her that I did not feel confident. I don’t have any background in this kind of work. I agreed to translate it, but told her that she would need to review my work. I wanted someone to check that it was correct. She agreed. Bernard Bel put in a request, too. So I took that on, too.

I realised that the initial translations I did for Guy were my introduction to the world of ovi. When I started looking at it in its entirety, I realised that, for a woman, the grindmill is her own private universe. It is a place where she can speak her mind. Men did not interfere in this space. Women could share their joys and sorrows, talk about their lives and children, and so on, freely with their friends and the grindmill. They spoke about such a variety of subjects that translating the ovis felt like a challenge.

You might ask how I came to this conclusion without even starting to translate.

Well, they have a classification system spanning 70 typed pages. It is very detailed. I had gone through it. The diversity of subjects that women have songs about stunned me. To give you a brief overview, there are ovis about the Pandharpur wari, deities and gods and goddesses, motherhood, and their kin, immediate family, siblings and parents. Then there are songs about Sita, Savitri, Draupadi and Ambedkar. There are plenty of subjects.

The fact is that the worlds of the women singing these songs and mine are very different. So, I was unsure how to approach this. I was prepared for all the difficulties that were going to come my way. So I made a plan. I decided to read the lyrics and, wherever I got stuck or found them difficult, to ask the women who sang or collected these songs directly for their meaning. The field workers came to Pune quite regularly, so I was able to meet them. I must mention that Ubhe Bai (Tarabai Ubhe), Sonawane Bai, Kamble Bai, Bhalesain Bai, Maid (Jitendra) and Rajani helped me immensely with this work. I also referred to the Molesworth Marathi-English dictionary.

Regarding some problems

When the songs were collected, the women sat at the grindmill, ground the grain and sang the ovi. The fieldworkers wrote down what they heard. It is clear that they sometimes missed words or misheard something, as the grindmill was quite loud. They also had to write quickly. So, in a few places, they made errors while writing. For example, ‘Laavali’ instead of ‘Saavali’, or ‘Peta’ instead of ‘Pheta’. I did not realise there were such errors. But slowly, I could sense that something was off.

There are some recurring themes, such as devpooja (daily prayers), saasurwaas (abuse and hardships in the marital home), ahevpan (being married) and muraali (the man who takes a married woman back to her parents’ home). These cannot be translated into one word, and if you try to explain them, they do not fit into one line. So, we prepared a glossary of such words. I discussed it with Bernard, and we decided to include these explanations in the glossary.

There are certain customs and rituals with which not everyone may be familiar. For example, the Gaja Dance, performed by the Dhangars around Diwali, in which they appeal to all their deities. Another custom is Sanjai, in which people steal a portion of the newly harvested crop as a ritual. I had never heard of this before. I doubt if others knew either. So we retained these words without translations. The meaning was in the glossary.

Often, women refer to their father or brother as ‘Patil’ or ‘Deshmukh’. These are not their surnames, but they connote a higher status and respect. In these instances, I have kept ‘Patil’ as it is and added ‘an important person’ in brackets.

One of the most challenging aspects of translating ovis is the use of symbols, myths and analogies. We try to translate them and create meaning. However, the focus was on retaining their language and explaining the meaning. I was determined to keep their vocabulary as it is and provide an explanation alongside the translation. Consider the phrase जात्या ईसवरा, तू तर डोंगराचा ऋषी, माझ्या माऊलीवाणी हुरद उकलं तुझ्यापाशी, which translates as ‘I open my heart’. The phrase हुरद उकलं तुझ्यापाशी / hurad uklan tuiyāpāśī (I open my heart) comes up repeatedly and I just love this expression. One does not need much explanation. A woman can share her innermost feelings with the grindmill just as she would with her mother. The grindmill does not question her or talk about it to anyone else. It remains secret. This makes things much easier.

However, in one song, the singer warns her daughter about a ‘thorny plant’ in her brother’s courtyard. I wasn’t sure if people would understand the hidden meaning. So I asked the singer to explain. They said that there are young boys in my brother’s family. One should therefore be alert and not act foolishly. We therefore kept the name of the thorny tree and added ‘beware’ in brackets.

I have included notes wherever I felt the need for an explanation. They also helped me later because there were so many ovis. And if you ask me, I can’t remember a thing right now!

In one ovi, the singer says that when the father was marrying off his daughter, he did not ask about the village to which she was going. It’s as if the cow had left her home for the butcher’s shop. In these two lines, she has explained her whole life and future, and the hardships she is going to face.

If you ask me to choose a favourite couplet, it’s impossible. For me, every ovi is special. However, there are some simple couplets that have always been my favourites. One says that Vitthala is my father and Rakhumai is my mother. Chandrabhaga is my sister-in-law, who washes my feet whenever I arrive. In just two lines, they capture their idea of happiness and the way they imagine respect and love from the family. In another couplet, Rukmini asks Krushna how his shawl got wet. Teasing her, Krushna says that he visited the tulsi ban (a tulsi plot in the courtyard) and that it got wet with dew drops. (The story goes that Tulsi, the plant, was Krushna’s beloved, which angers Rukmini, his lover.) I like the way he reminds her that she has a ‘savat’ (his second wife/lover). In response, Rukmini prays that summer will arrive sooner and the tulsi plant will turn into firewood. There are so many ovi poems like this that it is difficult to select just a few.

While translating a recent ovi, I was completely clueless. It said that Ravana had schemed to abduct Sita, but that Sita had refused to drink water from a cup made of Palash leaf. I did not understand what this meant. I talked to Maid, who suggested that Sita was so loyal to her husband Ram that she refused to drink water from a Palash leaf, a male word in Marathi. I wrote a short note to this effect. I’m not sure who it will help. You see, when Guy started doing this work, it was intended for a Western audience. I feel that I have not yet come out of that frame of mind of translating for a Western audience. We Marathi people do not need these explanations. But they might help those from other states.

Q: It’s been 30–40 years since you started this work, and it still continues. Have you noticed any changes in yourself as the translator?

If I had the chance, I would change certain words I used in my initial translations. I still find myself getting tied up in knots sometimes. I’m not sure if I have the time for that. I cannot say that I fully understand everything, but I have a much better grasp of it now. There are still difficulties, but I have learnt a lot through this process. I have gained a lot of knowledge. I must mention Jitendra Maid here. He was part of the original team that collected these songs. He travelled extensively to the most remote corners of the country, staying with people and sharing their lives. This means he has a much better understanding of the contexts and imagery of the songs.

My process is as follows: I read the complete set, discuss it with Jitendra, and then I translate it. Then we go through the entire translation and discuss it again. Sometimes, he points out places where he feels the translation does not convey the right meaning, or where there are gaps. It’s almost as if he has a sixth sense for this. He is very perceptive in this respect.

Q: What is the significance of Ovi in Maharashtra and of other such songs that women sing today?

I see this as a valuable resource for women. Through PARI, it reaches national and international platforms. I have a great sense of satisfaction. How else would these songs reach so many people? I see them as a form of wisdom and art. I admire their observations, their connections and their knowledge of nature, the stars and constellations, farming and the natural cycle of rain, winter and summer. They have deep knowledge as well as practical skills and application. I am awestruck when I read their words. There is one section called ‘Pandharpurchya Watevar’ (On the Road to Pandharpur). In it, women describe all the villages and landmarks they pass on their way to Pandharpur, such as a river on the left or a temple at the entrance. This may have changed over time. However, I still feel that one could draw a map of the route based on these ovis. It is so detailed!

The scope of their world, imagination and observation is mesmerising. This should reach more and more people. What more could we ask for?

Q: This work was initially intended for a Western audience. But today, many people here have also lost touch with this cultural space. Villages are changing and rural culture has transitioned too. Where does the ovi fit into this?

If you ask me about translations, not much has changed. I have continued working with that mindset. You are bringing this work to an international audience even today. Some of the explanations and notes are for my own use.

The more I translate and read these songs, the more I marvel at their wisdom. This work has given me immense pleasure. I am happy that my efforts help to bring their work to the attention of a wider audience. They used to thank me for translating their words so that more people could listen to and read them. Now, thanks to PARI [People’s Archive of Rural India], it has reached a much wider audience. The nature of the work has changed.

Although Marathi is the common language of Maharashtra, peasant singers often assign unusual semantic contents to words and phrases, along with implicit references to events and behavioural patterns characteristic of their world. Therefore, the corpus of grindmill songs needed to be strongly structured to enable systematic analytical work. In addition, spoken/sung language requires the sharing of transcription and spelling conventions for the sake of text consistency (in Devanagari script). I trained the team in the use of a relational database linking texts, performers, locations and semantic classification (

Although Marathi is the common language of Maharashtra, peasant singers often assign unusual semantic contents to words and phrases, along with implicit references to events and behavioural patterns characteristic of their world. Therefore, the corpus of grindmill songs needed to be strongly structured to enable systematic analytical work. In addition, spoken/sung language requires the sharing of transcription and spelling conventions for the sake of text consistency (in Devanagari script). I trained the team in the use of a relational database linking texts, performers, locations and semantic classification (